English in England: we should celebrate different languages, not write hate mail about them

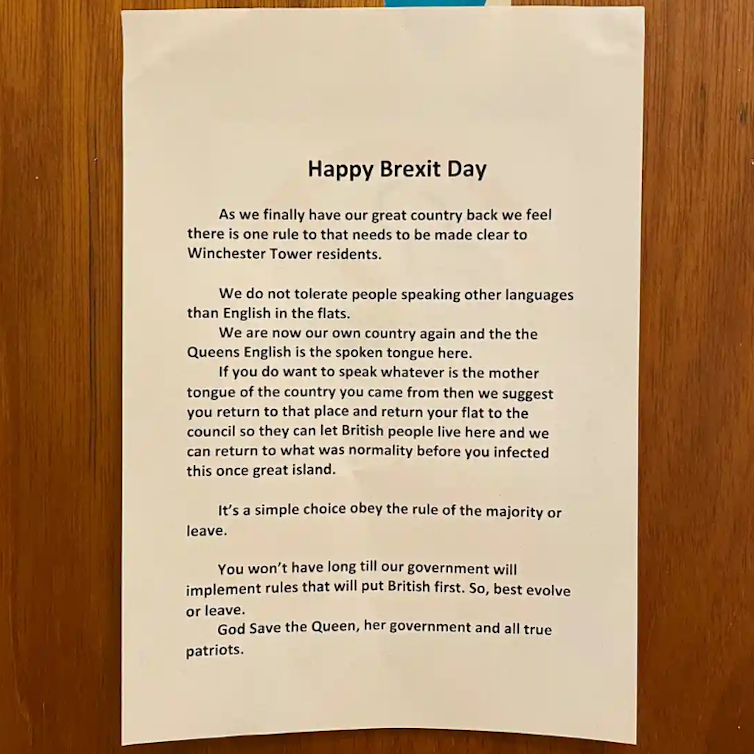

On the day that the UK left the European Union, a badly punctuated anonymous note was pinned to doors on the Winchester Tower block of flats in the city of Norwich, in the east of England. The message was directed at residents from abroad who had “infected this once great island”, informing them: “We do not tolerate people speaking other languages than English in the flats”, and that they should “obey the rule of the majority or leave”.

Police are treating the note as a racially aggravated hate crime and there have been widespread expressions of solidarity from local residents.

This strong response is somewhat surprising, since the demand that migrants should use the majority language – even in the privacy of their homes – has often been put forward by governments, and not just in the UK. As home secretary in the government of Tony Blair in 2002, David Blunkett told Asian citizens they should use English at home.

A similar demand was made by one of the parties in the German coalition government in 2014 and, in the same year, one of the largest Dutch parties ran an election campaign with the poster: “In Rotterdam we speak Dutch.”

At the same time, accounts of people on the streets of Britain being verbally or even physically attacked simply for speaking their native language in public have become depressingly frequent. A YouGov poll published a few days after the poster appeared found that 26% of people in the UK feel either “very bothered” or “fairly bothered” when they hear people from a non-English speaking country talking to each other in their own language.

Ever since a Bulgarian colleague told me how someone had screamed “Fucking Polish” at her and her husband in the street, I’ve been trying to work out how I would respond in a similar situation. Ideally, what I am after is the perfect one-liner that will not only shut the other person up but make them reflect on their attitude, repent of their ways, and, in general, turn them into a much better and nicer person.

And then I came across what, at first glance, seemed to be the ultimate comeback in a story I’ve seen in so many versions that it is probably an urban legend. In this story someone – in one account it’s a young mother wearing a Niqab, in another, it’s someone in Arizona making a phone call – is accosted by an aggressive stranger with some version of “stop speaking foreign muck” or: “if you want to speak Mexican, you should go back to Mexico”. The deadpan response is some version of: “Actually, I was speaking Welsh/Navajo – if you want to speak English, go back to England.”

Nothing kills off a joke like analysing why it works – but in this instance, I’m afraid I have to play the killjoy. The punchline of this story allows us to see the original remark as ignorant and offensive because the language in question is an indigenous one. This bestows on the speaker not only the right to use it but actually a kind of moral superiority.

But this also makes it problematic, because the logical next step is that my Bulgarian colleague must be in the wrong: at no period in time, to my knowledge, was there an indigenous Bulgarian-speaking population in Southampton. No perfect comeback for her – or me – then.

But what if the Navajo-speaker had made her phone call from Aberystwyth, not Arizona? And what if the Welsh mother was living in Wisconsin but still wanted her baby to grow up knowing its mother tongue and heritage language? Would that somehow put them in the wrong and the aggressive stranger in the right?

How many languages do you speak?

Many native speakers of English appear to assume that when someone chooses to speak a different language, it indicates that they are incapable of using English. The tepid response from the prime minister, Boris Johnson, to the Winchester Tower incident suggests he shares this view.

Like most stereotypes, that assumption is statistically highly likely to be wrong: according to the 2011 census, more than 98% of the UK population is able to use English well or very well. But many can and do use other languages in addition to English. They may find it more practical in certain situations or want to pass a language on to children. And that in no way takes away from their ability or willingness to use English.

In fact, far more people in the world know more than one language than are monolingual – and this has been the case ever since humans were first able to speak. Our brains and neural networks are physically configured for this purpose, and using this capacity brings multiple benefits.

It goes without saying that it is impolite – at least in situations where it can be avoided – to use a language that someone who is part of a conversation does not understand, because it excludes them. But these demands and attacks are not about feeling excluded, they are about regulating other people’s behaviour and objecting to anything that seems different.

Speaking in tongues

Which brings me back to the satisfaction we get from the Welsh/Navajo punchline. To me, this rather uncomfortably suggests a mindset which gives someone the moral right to proudly display their identity because “their people” have occupied the same patch of earth for many generations.

If, on the other hand, they themselves or their parents were the ones who brought their languages and identities with them from “foreign parts”, does that mean they should try to erase them as quickly as possible, renouncing the benefits that bilingualism and biculturalism would bring them?

I’m still searching for my perfect response, but a few weeks ago, I found one that will do in the meantime. It comes from a tweet from @AGlasgowGirl, whose mother was once confronted by a man demanding she speak English, not Punjabi.

I take huge pleasure imagining the residents of Winchester Tower – regardless of their gender, origin, or native language – bringing the stairways and balconies to life with animated and graphic debates of the relative merits of different period products. Loudly. Often. And, of course, in the “Queen’s own English”.![]()

Monika Schmid, Professor of Linguistics, University of Essex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.