Public engagement is not only about people and two-way communication. It can be about objects and how individuals feel and respond to that object; how trauma can be released as a result of engagement.

In this blog Jonathan Lichtenstein provides a reflective account of trauma endured by his father during the Holocaust in Germany. Public monuments allow for engagement that is non-verbal, unpredictable and individually experienced. They’ve in a way helped his father find a certain kind of peace. This blog is based on Jonathan’s new book: The Berlin Shadow.

A road trip to Berlin

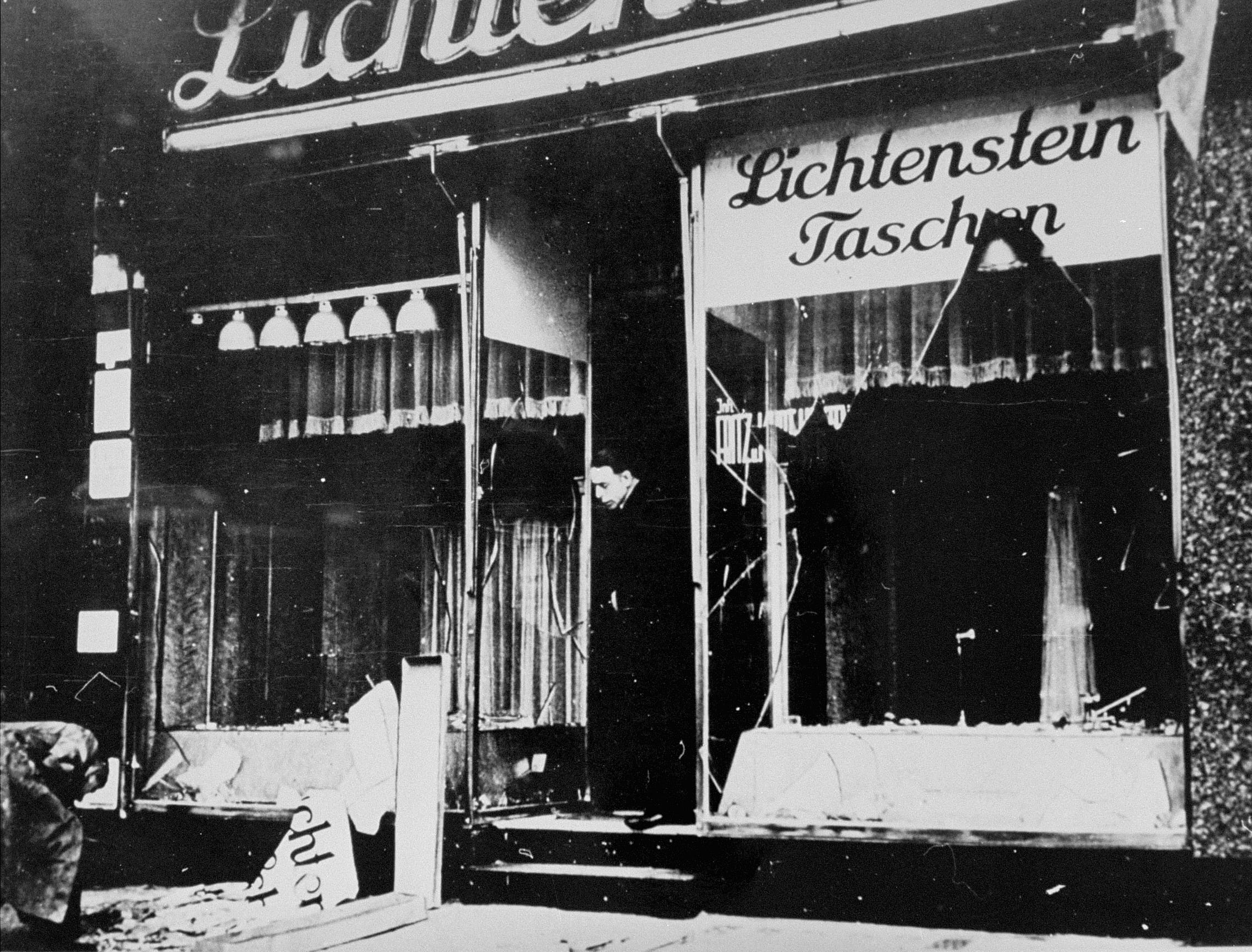

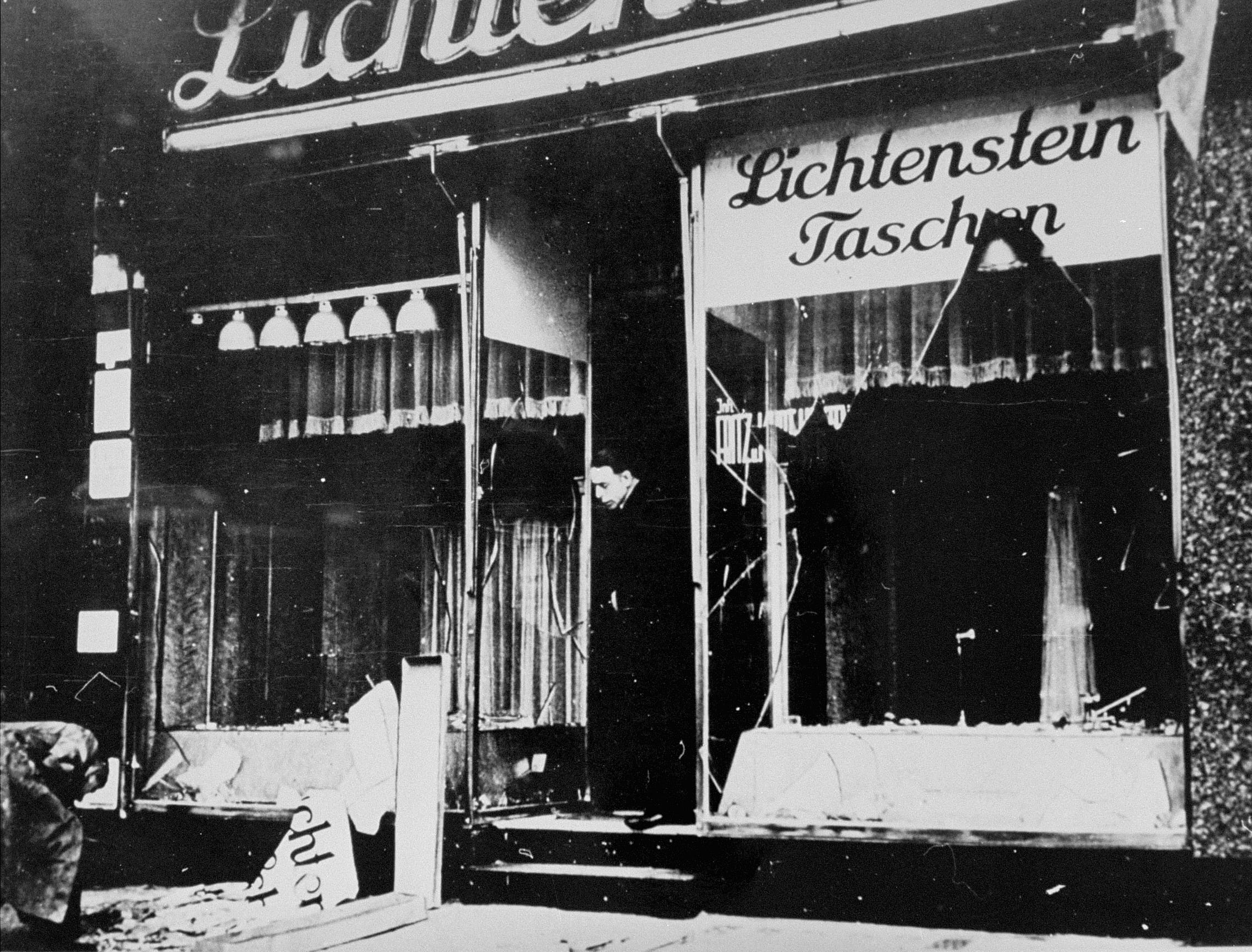

Five years ago, I took a road trip with my father from Wales to Berlin. My father, the eldest son of a Jewish family, had escaped from Nazi-Germany on one of the kindertransports in 1939. His mother managed to get him on one of the last trains out of Berlin. He was 12. He travelled alone. He left his family behind. Some he saw again - most he didn’t. All his life he refused to talk about what had happened to him. He considered himself exceptionally lucky.

Our trip together followed my father’s journey of escape in 1939, but in reverse. We drove from Wales, to Harwich, took the ferry to the Hook of Holland, visited Amsterdam and a town called Bad Bentheim and then stayed in Berlin.

In Berlin we found things that my father remembered, the house he grew up in, cafés he’d eaten in with his family, his father’s grave situated in the largest Jewish Graveyard in Europe, one of his father’s shops, the Tiergarten where he learned to ride a bike, the station platform he left from. We visited public monuments such as The Jewish Museums Berlin and The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. We also visited Sachsenhausen concentration camp. These events meant my father experienced memories and feelings that he had buried for many years. Some were blindingly painful, some surprisingly joyful.

I knew that something powerful had happened during our trip though I could not articulate it. I understood I did not understand what had happened. I was awarded a Leverhulme Research Fellowship to spend a year writing about what I hadn’t understood. In the end the six-day trip took several years to write up.

Trauma: passing through the generations

The reason that the book took so long to write was because I had to trace the impact of the traumatic event upon my father but also on myself. I found this very difficult to think about. I began to realise that I was writing about the way that a trauma that happens to one person can pass down the generations. This is well known in theory and I’ve since become aware of the idea of ‘the Second generation’ but I didn’t realise how affected I’d been by my father’s difficulties – how I’d somehow imbibed aspects of his trauma – even though I had not lived through them. They had been secretly, and in silence, communicated to me. The word ‘commune’ is one that became useful to me. He had somehow communed with me and in so doing had allowed me to glimpse what had happened to him.

Public Monuments allow for engagement

As I wrote about our journey together, I came to realise the way various public monuments allow for an engagement that is non-verbal, unpredictable and individually experienced. Each person has their own reaction to a public monument. These monuments allow the vocabulary of the body to be engaged. By this I mean that they allow complex and ambivalent feelings to be experienced and felt, ones that cannot be clearly articulated verbally. The language of the body has its own eloquence. I spent a long time describing what it felt like in these moments with my father, feelings of pressure, compression, heat, the sense of leaving my body, a clawing at my skin, immense stillness, a swirling of the mind.

Much of our trip together was spent in a kind of full-up silence. Writing about this silence, and about how one writes about, ‘that which is impossible to comprehend’, became very important to me. It made me realise what we all know that fraught and full silences are impossible to describe yet contain profound meaning.

The book

I used several technical ideas in the book - The Berlin Shadow - which linked to my playwriting experience. I wanted the dialogue to read as though it was blank verse and I wanted to develop my interest in contemporary tragedy. I teach tragedy and most of my creative work uses this form. Tragedy is one of our oldest aesthetic forms - it’s ancient. I like to keep my work within its constraints as it is a suitable form for holding and containing ambivalent and contradictory feelings. It is a container where deepest feelings of catastrophe can be looked at safely. For this reason, tragedy is an optimistic structure. It illuminates the points where we can collectively learn, so that certain behaviours can be avoided in the future.

The variety of public and private monuments that acknowledge the Holocaust in Germany allowed my father to gain a certain peace. Until we went on the trip my father had suffered, for his whole life since the kindertransport, from vivid and disturbing nightmares. These involved him shouting out at night as well as a physical restlessness that made it impossible for him to rest even while sleeping. He was a tortured soul. After the trip finished, he was able to sleep for the first time. He died very peacefully nearly two years ago. It was night. I was with him. He smiled as he died. He wasn’t frightened at all.

Professor Jonathan Lichtenstein is Professor of Drama at the University of Essex. His new book, The Berlin Shadow, was published in the United Kingdom in August 2020. The book has been translated into a number of languages including Danish, German, Dutch, Italian and French.

‘A unique and intimate addition to the literature about the Holocaust’ Kirkus reviews November 2020.