Scots less likely to identify as ‘European’ than others in the UK, survey reveals

Scottish election results have put pressure on the UK government at Westminster to authorise a second referendum after pro-independence parties won an overall majority in the Edinburgh parliament.

It seems likely Boris Johnson will refuse this for now and so it may be there is no movement until after the next general election. Eventually, if the Scottish government did win a second referendum, it would negotiate independence from Britain and subsequently apply to join the European Union.

A key argument made by nationalists is that an independent Scotland would prosper inside the European Union much as similar sized countries like Ireland and Denmark have done in the past. However, this strategy has overlooked a problem – namely, that the Scots are the least likely to identify themselves as Europeans in all of the three nations which make up Britain.

This is evident in our recent nationally representative survey of over 3,000 voters in Britain. The survey was conducted by DeltaPoll, and it is nearly three times larger than the average opinion poll.

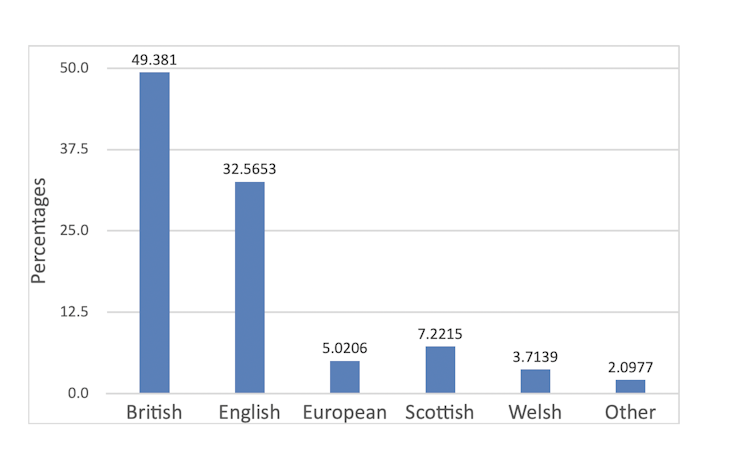

In our survey, just under half of the respondents described themselves as “British” and another third as “English”, with the self-described “Scottish” the third-largest group. Just one in 20 respondents described themselves as “European”.

National identities in Britain

A separate question asked how respondents voted in the 2016 referendum. A majority of all of the identity groups voted to remain in the EU, with the sole exception of the English. Some 61% of them voted to leave, and it was enough to decide the outcome. English identity is a strong marker of Brexit support.

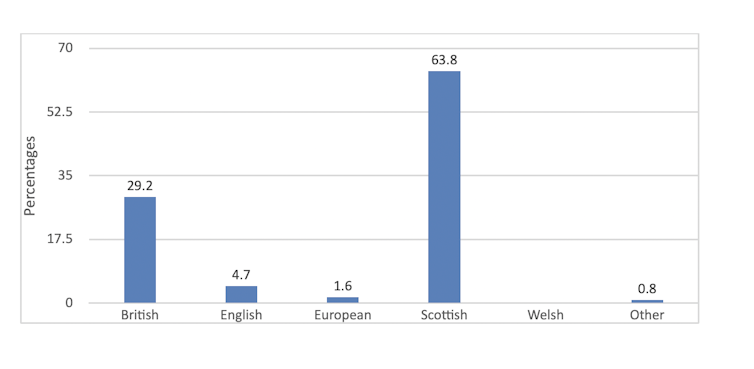

If we repeat the analysis, but this time looking only at respondents who live in Scotland, the picture is very different. Almost two thirds of the people described themselves as “Scots” with just under a third describing themselves as “British”. Perhaps more surprisingly, only 1.6% of respondents in Scotland identified themselves as Europeans. That’s a much lower proportion than in the rest of Britain.

National identities in Scotland

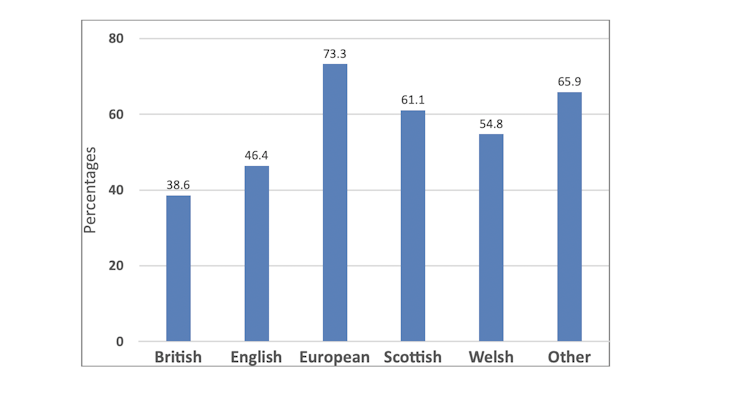

What are the implications of this for a second referendum on independence for Scotland? We asked the following question, again across the whole of Britain: “Should Scotland be allowed to hold a second referendum on independence from the United Kingdom?”

The most enthusiastic supporters for a second referendum turn out to be the “European” identifiers – no doubt because they believe that if independence is achieved, it will lead to Scotland joining the EU. It is also noteworthy that while there is a clear majority of Scots identifiers supporting a second referendum some four out of ten of them do not want one.

Support for a second independence referendum in Scotland across identity groups in Britain

In this respect, attitudes are strongly influenced by what happened to respondents during the COVID-19 crisis. No less than 64% of those reporting serious financial problems favoured a second referendum, compared with only 38% who reported no financial problems at all. The logic of this is simple, if an individual had a really rough time coping with the pandemic they want a change, and this desire extends to the constitutional order in Britain.

As a result, these individuals favour another referendum on independence for Scotland. If, however, they survived the pandemic without any financial problems, they tended to oppose constitutional change. That said, this finding is unlikely to boost support for a second referendum, since only 11% of Scots identifiers reported having serious financial problems compared with 62% who stated that they had no such problems.

Independence – or just the referendum?

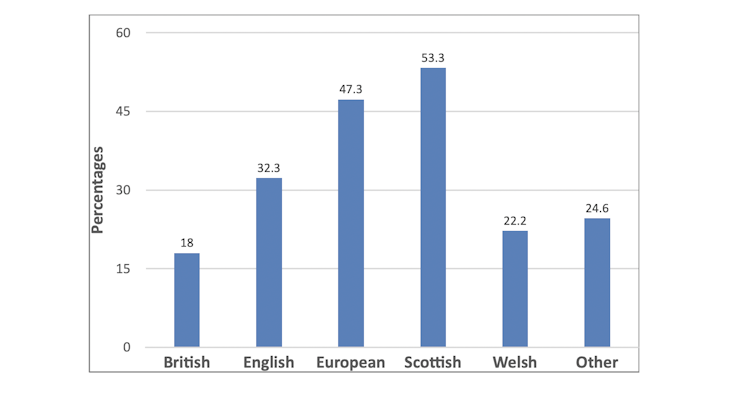

We should also be careful not to assume support for a second referendum is the same as support for independence. Not surprisingly, a majority of Scots identifiers favour independence in our survey – but significantly fewer than the number who support a referendum. All of the groups, apart from the Scots identifiers, were more likely to oppose independence than to support it, and this included the Europeans. The least enthusiastic were the British identifiers, who, as we know, are the largest group.

Support for independence across identity groups

Faced with the reality of a decision on whether or not Scotland should become an independent state, as opposed to a question about the right to choose their own future, many Scots clearly have misgivings.

Over the past few months Scottish polls on independence have shown considerable volatility. In early December, when the UK was just beginning the vaccine rollout, 47.5% said they would vote yes in an independence referendum and 41.5% said they would vote no. Five months later, in early May, these numbers were reversed with 42.9% indicating they would vote yes and 47.1% saying they would vote no.

It appears that the UK’s successful vaccine rollout combined with the EU’s difficulties in implementing a similar program combined with heavy-handed threats to cut off vaccine supplies to the UK have taken a toll on the EU’s reputation. They may also recall the painful years of negotiation that followed the vote to leave the EU in 2016.

If the Scottish nationalists did win a referendum on independence by the small margin that current polling suggests might occur, then a declaration of independence would probably create a backlash in the rest of Britain. This would make the negotiations over Brexit look easy by comparison – and the recriminations would probably last for years.![]()

Paul Whiteley, Professor, Department of Government, University of Essex and Harold D Clarke, Ashbel Smith Professor, School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.