This article first appeared in VOXEU 7 April 2022

The strength of the labour market recovery from Covid-19, and the extent of the economic scarring, depend on both job creation and whether job seekers look for jobs in the growing sectors of the economy. This column uses a novel dataset to provide direct evidence on the types of jobs sought by workers during the pandemic. It shows that workers increasingly targeted jobs in expanding occupations and industries. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of workers targeted jobs in declining occupations and industries. These workers tend to be the most disadvantaged: the non-employed and those with the lowest education qualifications.

The coexistence of a large number of available jobs and many jobless workers is often seized upon as evidence that the jobless are not willing to work. Another possibility is that there is a fundamental mismatch between the types of jobs that firms are advertising and the types of jobs that workers are looking for or have the qualifications to perform. These ideas have come to the fore amid stories of labour shortages following the Covid-19 pandemic, and seem to motivate policy measures such as the UK government imposing benefit sanctions on job searchers who fail to look for jobs outside their past sector or occupation. Analysis in Anayi et al. (2021) suggest unemployment from mismatch is a very real prospect for the US and UK in the wake of the pandemic. This may have consequences for not only labour markets but aggregate productivity too. Patterson et al. (2016) argue that labour market mismatch explained around two-thirds of the shortfall of UK productivity relative to trend after the 2007-08 Great Recession.

Previous attempts to measure so-called ‘mismatch’ unemployment have faced the challenge that data on the type of jobs sought by workers is often not readily available. Often researchers are forced to assume that job searchers look exclusively for jobs in their past sector or occupation (Sahin et al. 2014). In recent work (Carrillo-Tudela et al. 2022), we look at these questions more directly by exploiting a rich and novel data set: the job-search module of the UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS). This module asked respondents who were looking for a job to list the occupation and industry that they were targeting. These data are rich in information that can guide our understanding of unemployment dynamics and inform the appropriate policy response.

Workers show flexibility in the type of job they search for

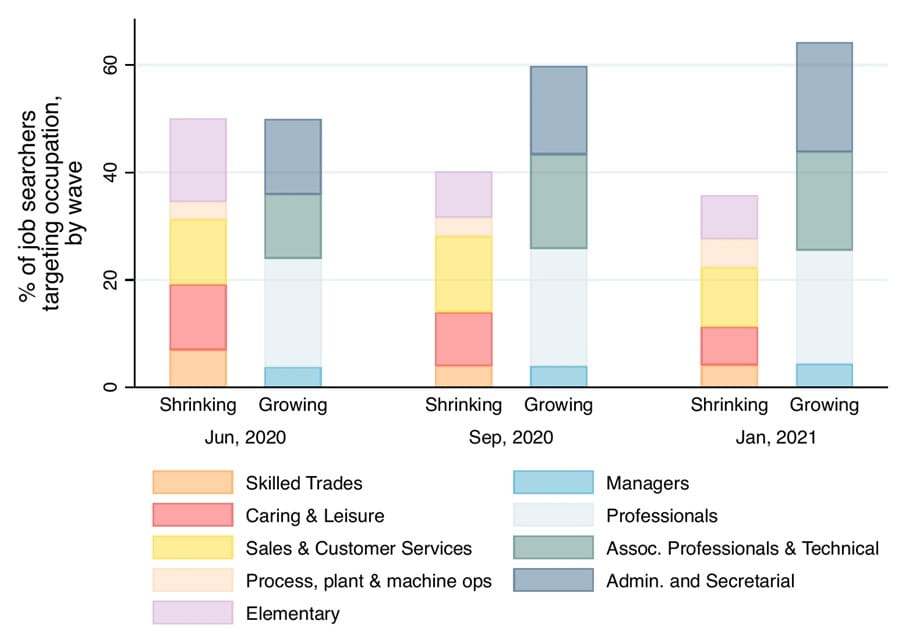

Our first key finding is that job seekers significantly adjusted their job search in favour of the industries and occupations that expanded during the pandemic. As of June 2020, about 58% of job seekers targeted occupations that were experiencing increases in their employment levels during the pandemic. This proportion increased to 70% by January 2021, as illustrated in Figure 1, which shows the percent of job seekers listing a given occupation as their first preference in their job search. The growing occupations were those which typically require higher skills, offer higher wages, and provide more opportunities to work from home. Across industries, about 41% of job seekers targeted expanding industries in June 2020 and this proportion increased to 50% in January 2021. So, even in the absence of benefit sanctions, workers endogenously change their search direction to target expanding occupations and industries.

Figure 1 Workers increasingly target expanding occupations

Disadvantaged workers more likely to target declining industries and occupations

However, we still see a significant proportion of job seekers targeting declining occupations and industries: the question is why? Our second key finding is that those at the margins of the labour market were most likely to target declining industries and occupations. For example, we find that non-employed workers were significantly more likely to target a declining industry and occupation in their job search.1 Those with the lowest education levels were also significantly more likely to target declining occupations. These results hold true even when conditioning on past occupation or industry, so they are not simply a reflection of attachment to previous jobs. However, attachment does play a role as workers from a declining industry (occupation) are more likely to target a declining industry (occupation), suggesting these workers may be trapped in ‘bad job’ cycles. The flip side of this is that employed or higher education workers are more likely to target expanding industries and occupations, as are those who have previously worked in these jobs, implying a more ‘virtuous’ job-cycle for these workers.

It takes two to tango: Workers’ willingness to switch not always matched by firms’ willingness to hire switching workers

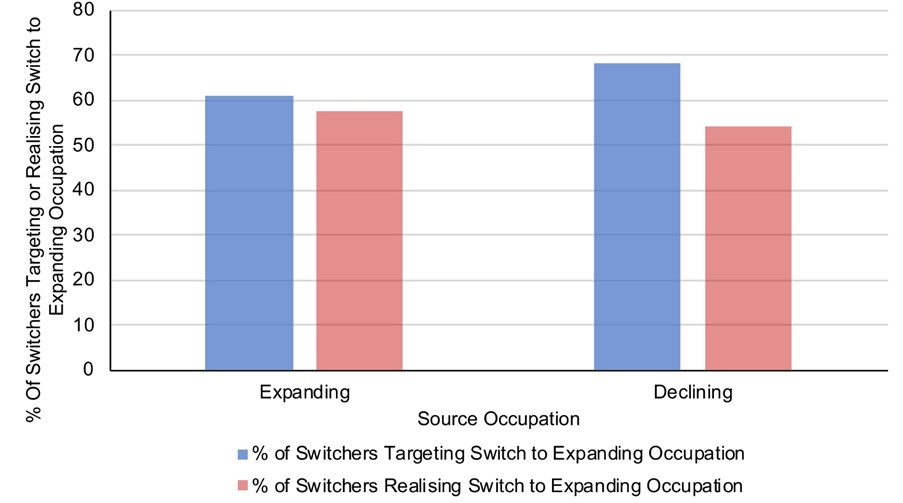

Third, and finally, there is a substantial mismatch between the type of career transitions workers are looking for and the type of transitions they make. Among those targeting any occupation switch, the proportion of workers successfully transitioning into an expanding occupation was lower than the proportion of job seekers targeting a switch into an expanding occupation, particularly for those individuals coming from declining occupations (Figure 2). This suggests the presence of a glass ceiling that inhibits workers in declining occupations from realising their desire to switch into expanding occupations.2 This should perhaps not be a surprise given worker reallocation is an equilibrium outcome of worker and firm behaviour. Firms must be willing to hire workers from other sectors, as well as workers being willing to search for jobs outside of their sector, for a switch to occur.

Figure 2 Targeted versus realised occupation switches

Implications: Helping workers and employers bridge the gap

The three key findings above are rich in implications for the related policy debate. First, we saw that workers, including the non-employed, endogenously change their search direction towards expanding parts of the economy without any impetus from the benefits regime. This calls into question measures to impose benefit sanctions on unemployed workers who do not search outside their previous occupation and sector.3

Second, we saw that those workers that did target declining occupations were more likely to be non-employed or have low education qualifications. This points to the importance of retraining/education programs for the jobless, as well as the provision of job search assistance. During the pandemic, the UK government provided funding for adults to acquire an A-level equivalent qualification if they did not already possess one. However, it is not clear this is sufficient to bridge the gap between the skills demanded by employers and those possessed by job searchers.4

The importance of retraining schemes is also suggested by our third finding showing the workers from declining occupations switch into expanding occupations less frequently than they desire. Occupation mobility may therefore be inhibited by firms’ willingness to hire workers who lack previous experience in a particular occupation or industry. This suggests policies that target firms as well as workers could have a role in encouraging reallocation. This could include the provision of wage subsidies for firms that retrain or hire unemployed workers in roles they don’t have previous experience in. Stantcheva (2022) highlights the positive record of such employer-focused active labour market policies in the US. Fujita et al. (2020) also highlight the potential role of wage subsidies of the young in promoting an optimal allocation of workers across sectors.

In short, our work shows that workers do tend to search for jobs in the growing parts of the economy. However, the most disadvantaged workers may require assistance to successfully obtain these jobs and employers can play an important role in this.

References

Anayi, L, J M Barrero, N Bloom, P Bunn, S Davis, J Leather, B Meyer, M Oikonomou, E Mihaylov, P Mizen and G Thwaites (2021), “Labour market reallocation in the wake of Covid-19”, VoxEU.org, 13 August.

Carrillo-Tudela, C, A Clymo, C Comunello, A Jaeckle, L Visschers and D Zentler-Munro (2022), “Search and Reallocation in the Covid-19 Pandemic: Evidence from the UK”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17067.

Duchini, E, S Stefania and A Turrell (2020), "Pay transparency and gender equality", CAGE Online Working Paper Series 482, Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy (CAGE).

Fujita, S, G Moscarini and F Postel-Vinay (2020), “The labour market policy response to COVID-19 must leverage the power of age”, VoxEU.org, 15 May.

Patterson, C, A Sahin, G Topa and G Violante (2016), “Working Hard in the Wrong Place: A Mismatch-Based Explanation to UK Productivity Puzzle”, European Economic Review 84: 42-56.

Sahin, A, J Song, G Topa and G Violante (2014), “Mismatch Unemployment”, American Economic Review 104(11): 3529-64.

Stantcheva, S (2022), “Inequalities in the Times of a Pandemic”, Working Paper.

Endnotes

1 See results in Table 2 of Carrillo-Tudela et al. (2022).

2 The idea that there are social and economic barriers preventing mobility between occupations is looked at extensively in the gender earnings literature (see Duchini et al. (2020) for example).

3 The UK Government did exactly this in January 2022: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-60149016

4 An A-level is typically the highest qualification obtainable during secondary education in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Details of policy announcement summarised here: https://ifs.org.uk/publications/15405