Six reasons why the Tories lost the Chesham and Amersham byelection

The recent Chesham and Amersham by-election was a major shock for the Conservative Party, which had trumpeted recent polls showing its lead over Labour as proof of Boris Johnson’s ability to “defy political gravity”“. But, in this – previously solidly Tory – constituency in the Conservative Party’s south-eastern heartlands, the Liberal Democrat candidate, Sarah Green, turned a 16,223 Conservative majority at the 2019 general election into a Liberal Democrat majority of 8,028.

The loss of the Hartlepool by-election by Labour in early May, coupled with this striking victory for the Liberal Democrats, shows just how volatile electoral politics has become in Britain. That said, Chesham and Amersham is a bigger shock than Hartlepool, because the latter was foreseen by the pollsters. By contrast, this result came out of the blue.

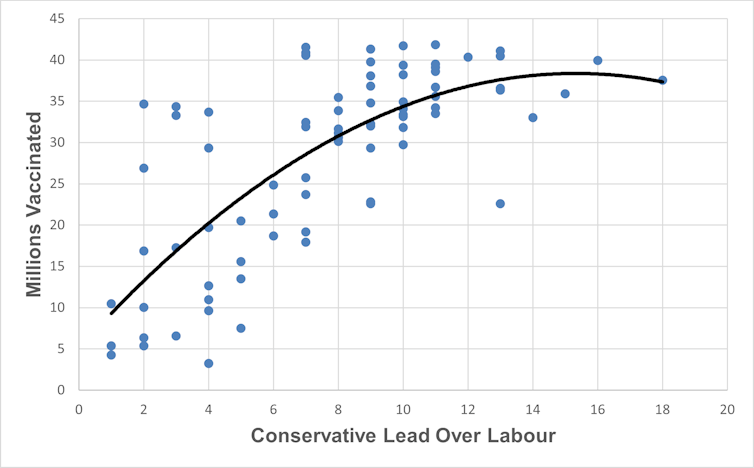

A number of factors explain the Lib Dems’ victory. Firstly, the halo effect arising from the vaccine programme has boosted support for the government, but as the figure below shows this has now worn off. Each dot in the figure represents a poll comparing the Conservative lead over Labour in voting intentions with the numbers of people vaccinated on the day the poll was published.

This lead grew rapidly as the numbers vaccinated increased in the early part of the year. But by late April the effect started to tail off and by the end of May it had disappeared. The lead is now narrowing again. This change has probably been reinforced by the government’s failure to achieve "freedom” day on June 21, which has disappointed a lot of people – including many backbench Conservative MPs.

A second factor is the spate of revelations from Johnson’s former chief adviser, Dominic Cummings, broadcasting the prime minister’s opinions about some of his colleagues. Normally voters would not pay much attention to rows like this in the “Westminster village”. But the revelation that the prime minister thinks that Matt Hancock, the health secretary is “fucking hopeless” – something which has not been denied by Number 10 – are so sensational that they received a lot of media coverage. The result is the appearance of a government in turmoil – and this means a loss of popular support.

HS2, planning reforms and Brexit

There are also local factors at work, particularly the impact of HS2 which goes right through the constituency and threatens to seriously disrupt life for many who live there. Wisely the Liberal Democrat candidate opposed the project, even though her party is in favour of it. This placed her Conservative opponent on the back foot.

There is also a wider discontent among “shire Tories” – traditional Conservative voters in small towns and rural areas – about changes in the planning laws, which could change the nature of housing development.

The fear among many natural Conservative supporters is that the government will hand over housing policy to the construction industry, which is primarily interested in building “executive housing” on greenfield sites. These firms are very reluctant to contribute to the infrastructure and social costs needed to support this policy at a time when local government is struggling with severe budget cuts. The concern is that beautiful countryside will be sacrificed to build unaffordable housing which might well turn into run-down estates.

A fourth factor is the perception that the government is focusing too much on the needs of its supporters in former industrial “red wall” constituencies in the north of England. To many this implies that “blue wall” constituencies in the rural and suburban south will be forgotten. This is the mirror image of the problem facing Labour, which is losing support in its traditional areas while gaining in affluent university towns in the south and east such as Cambridge, Norwich and Canterbury.

Labour’s problem in the 2019 election was considerably worse than that now facing the Conservatives, but this may well change in the future. Despite Labour’s poor performance in that election, it was strongly supported by young people, who may very well stay with the party in the future.

A fifth problem is the fallout from the very hard Brexit that Britain has ended up with. The debates on Brexit in the House of Commons showed there was only a relatively small minority of Conservative backbenchers supporting a complete break with the EU. When it comes to voters, more than 55% of people in the Chesham and Amersham constituency supported remain in the EU referendum.

This means that many Conservative Remainers are disillusioned with the result. “Get Brexit Done” may have been an effective slogan in the 2019 election, but the outcome looks increasingly problematic to many of them.

Tactical voting?

A final issue is the rise of tactical voting. One of the longstanding features of electoral politics in Britain is that supporters of the ideological right are united around the Conservative party, whereas supporters of the left are divided between Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the increasingly popular Greens. But the weakening of party attachments which has been going on for a long time means that tactical voting is growing in importance, particularly in by-elections.

Labour won more than 7,000 votes in the constituency in the 2019 general election and the massive loss of support for the party in the by-election suggests that a large majority of them switched to the Liberal Democrats. They supported the party that came second in the general election in order to beat the Tories.

By-election results are poor predictors of general elections so this tells us little about what might happen in 2024. But it does show that traditional Conservatives are as ready to switch parties as many Labour supporters.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.