“Do Not Burn Art”: Sri Lanka’s Artful Struggles

In July 2022, an unprecedented protest movement against corruption, immiseration, and impunity swept Sri Lanka and forced the President to flee the country. While the protest movement called itself “the Struggle” (Aragalaya and Porattam in Sinhala and Tamil), it was, more accurately, a volatile mix of multiple struggles by disparate groups – from Tamil families of the disappeared to Sinhalese army veterans, from paddy farmers to the urban middle class, from Muslim women to trans people.

One year on, a new exhibition at the University of Essex and a parallel exhibition at Harrow Arts Centre commemorate and contextualize these different struggles at a time of renewed austerity and repression. The exhibitions explore how the visual arts helped promote – and now help sustain – a more hopeful, pluralistic, and just politics for Sri Lanka. They do so by bringing together several Sinhalese, Tamil, and Muslim artists whose work tackles key ongoing struggles – for accountability, economic justice, religious understanding, and women’s rights. The exhibitions aim to raise greater awareness about Sri Lanka’s crises and struggles, as well as to highlight the important role played by contemporary artists.

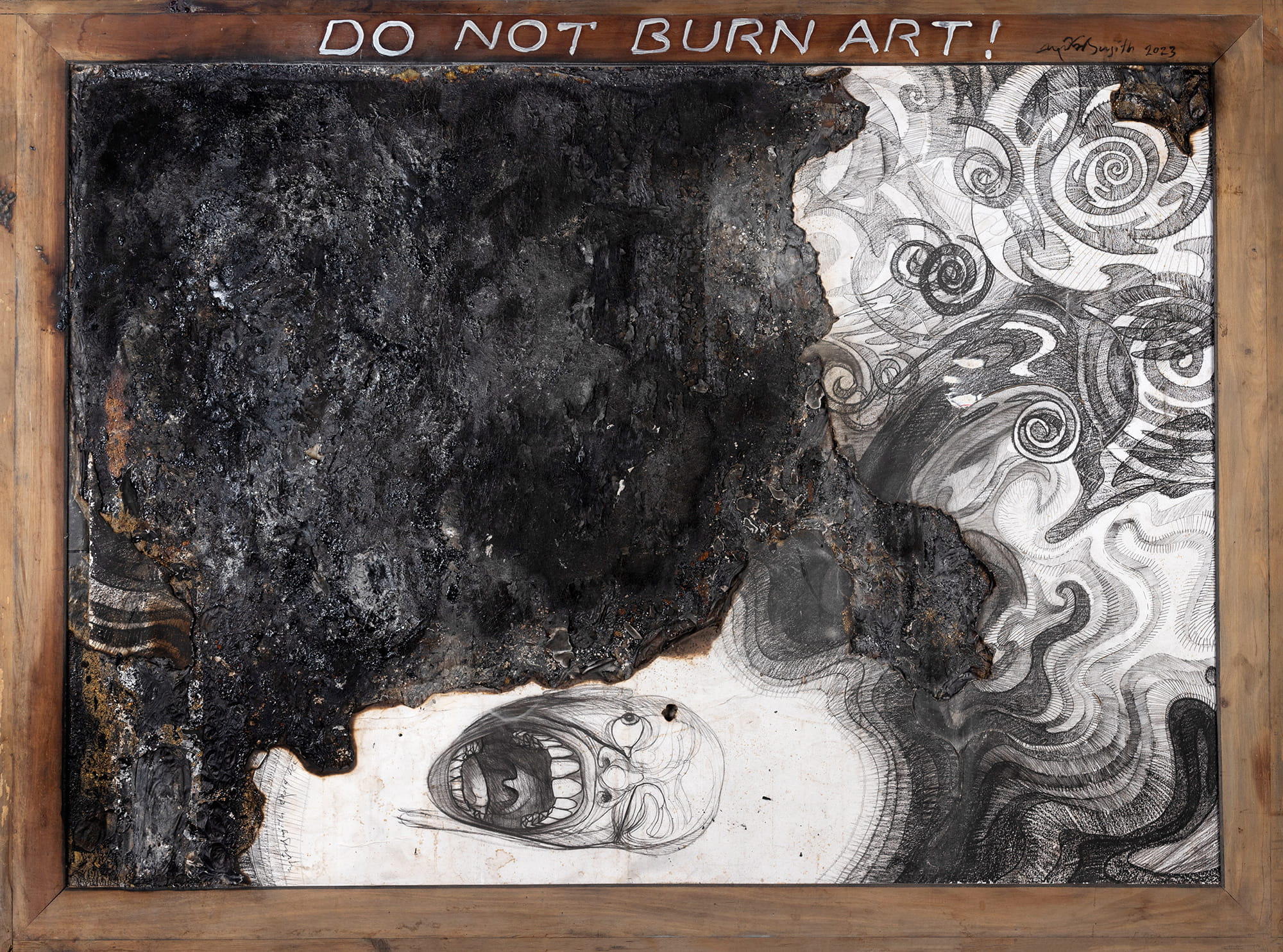

Both exhibitions feature recent work by the artist Sujith Rathnayake, who set up the GotaGoGama Art Gallery at the largest protest site in Colombo. At that gallery, Rathnayake painted posters, banners, and bodies, gave free art classes to children, and raised awareness of art. The gallery was burnt down by supporters of the President on 9 May. In response, Eshadi Yaddehiarachchi (with Rathnayake) painted “Do Not Burn Art” using ash from charred paintings and her own blood. Rathnayake later marked the gallery’s destruction by burning an earlier work (appropriately enough from his Hallucination series) and re-titling it “Artist’s Painting Set on Fire by the Artist.”

Rathnayake’s recent work focuses on how the new President quickly labelled protesters as “terrorists” and used the draconian, 43-year-old Prevention of Terrorism Act to suppress the protest movement. One painting in the exhibitions shows a protester on the ground holding a sign proclaiming “People’s Sovereignty.” The canvas is set into a large, rusting iron frame with words riveted on the top (“Prevention of Terrorism Act 1979”) and the bottom (“Enforced also during the economic crisis of 2022”). As Rathnayake explained to us: “I used metal frames to show how we are restricted and trapped by this old, rusted, outdated Act. … to show how state terrorism makes all of us who are subjected to it vulnerable.”

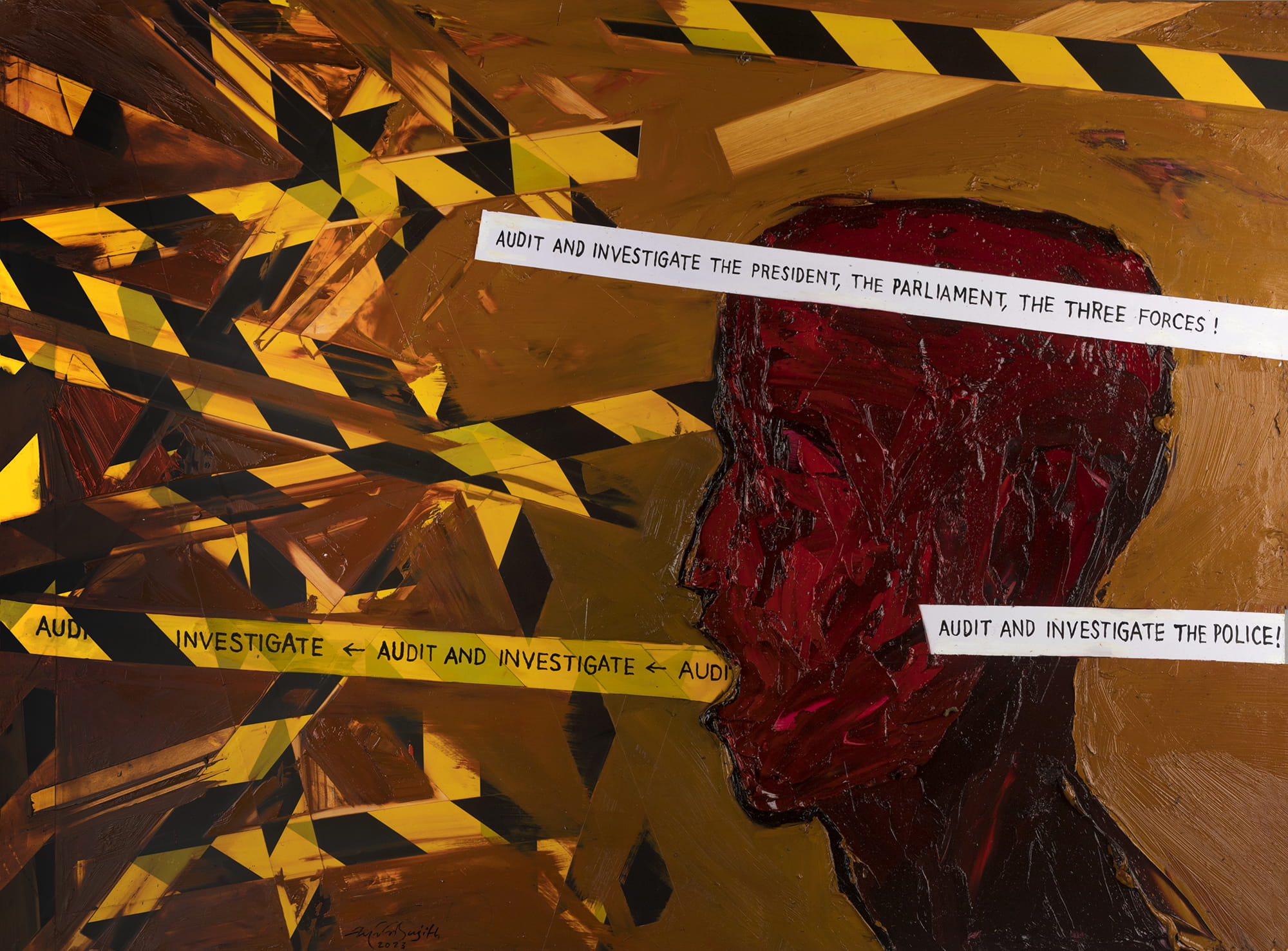

For the Harrow exhibition, Rathnayake painted several new works which will be exhibited for the first time. These works use police barrier tape to capture the severe limitations on freedom of expression and freedom of assembly that pervades Sri Lanka today.

To coincide with the Essex exhibition, the Essex Transitional Justice Network, Centre for Global South Studies, and Art Exchange are co-hosting a panel discussion on 6 July in which Rathnayake, Professor Sandya Hewamanne (Sociology), and Samanmali Alujjage Don (Sociology) will discuss Sri Lanka’s struggles. The panel also provides a comparative perspective: Dr Gavin Grindon talks about his work with protest art and “disobedient objects” in the UK and elsewhere; ESCALA curator Dr Sarah Demelo explores Essex’s remarkable collection of Latin American protest art; and Art Exchange curator Jessica Twyman discusses recent exhibitions of protest art on the university campus.